Gravity Works As WeWork Doesn’t; Now Plan B

WeWork pulled its colossally failed IPO, but still expects to complete it by year-end. Don't hold your breath.

Nearly four years after I wrote this report, WeWork has just announced it “substantial doubt exists about the Company’s ability to continue as a going concern.”

Want to know why WeWork failed? The better question is, how did it last another four years after a catastrophically failed IPO which revealed that its business model had always been fatally flawed. No, WeWork's value was in the hundreds of millions it made for its rabid banks and "smart money" buying and selling WeWork to and as investors. This also was obvious from the beginning, as I wrote in this report back in 2019.

Vicki Bryan, 8/8/2023

It's official: The We Company (WeWork) (WE US) has decided to pull its IPO for now, but still expects to complete it by yearend.

Don't hold your breath.

This comes just days after WeWork filed an amended S-1 announcing plans to list its new shares on the Nasdaq index even as its IPO valuation continues to dissolve. Reuters had reported on Friday that deal insiders were considering an implied equity valuation of just $10-12 billion, a stunning 78% drop versus the extravagant $47 billion floated since January. My analysis shows even $10 billion is too high.

So it's not surprising that long-term backer and top investor Softbank Corp (9984 JP), arguably the most responsible for WeWork's incredible equity valuations, had urged the company to scuttle the IPO given the "cool reception" it's been getting.

Yet WeWork is compelled to push on regardless, seemingly ready to concede to any termsto get a deal done because, I suspect, its financial condition is much more fragile than it has been trying to project. It has little time to waste and few alternatives.

If so, that means Plan B must already be in the works.

Either way, risk has intensified for WeWork's overpriced bonds.

How to Create a Capital Evaporation Community

WeWork isn't the first "ultimate unicorn" to come to market with ridiculous valuation expectations. But it is surprising how quickly this high flyer has fizzled in the cold light of day since most of its foibles have been chewed over for years.

Critics, myself included, have dressed down WeWork for most of its nine-year existence because it's actually not a new wave technology company as advertised nor even much of a disruptor. IWG PLC (IWG LN), a much larger, more seasoned rival, has been running the same kind of business since the late 1990s when it was the "WeWork" of the dotcom bubble with similarly overheated valuations. It also has battle stripes to show for it after plunging into bankruptcy with its US-based business when the bubble burst and then rising from the ashes to the profitable and well-capitalized operation it is today.

By comparison, WeWork is just another glammed up real estate company with slick marketing and lots of shiny objects to help it sell its overpriced office "space as a service," a deliberate play on "software as a service" to make it sound high-techy.

WeWork also is structurally compromised with an "asset-light" business model which has it committed to decades of leased space in expensive markets as it spends billions of dollars outfitting its office "communities" while relying on short term revenue typically coming in increments of months to a year at a time. This makes WeWork vulnerable to adversity since its targeted market groups of capricious freelancers and small businesses can easily melt back into their ether worlds should stalling economic conditions settle into protracted decline, which now seems increasingly likely. The co-sharing office concept is driven, after all, by the idea that people are free to work anywhere these days. So when times get tough they will take the cheapest path they can to survive--like back to Starbucks or their home offices.

Co-sharing office space really took hold as millions found themselves out of work and scrambling during the last recession, which was the worst in 80 years. WeWork was born in the trough of that cycle in 2010 and so has known only recovering economic and business conditions. Yet during its existence evolving during the longest economic recovery in US history, WeWork has not only failed to turn a profit, its losses have grown faster than its rapidly escalating revenue. WeWork reported a net loss of $1.93 billion on $1.82 billion in revenue generated in 2018, with continued losses tracking a similar range through the first half of 2019.

WeWork has attempted to offset this risk in the service of selling how durable is its model by featuring "enterprise" clients which are larger companies that can rent floors of space and contribute now roughly 40% of its revenue. The trouble is such space also can and likely will disappear in a business downturn as easily as it was added by companies that logically viewed this flexibility as a key advantage to help preserve their own resiliency.

All this challenges WeWork's assurances that it can survive a business downturn simply by shutting down its growth engine sufficiently to idle its way to breakeven and even profitability. This response could indeed slash some of the company's operating and development costs, but not its own prohibitively high lease expenses which comprise the bulk of its overall costs and claimed more than 2/3 of its $1.8 billion in annual revenue in 2018. That bill has climbed to $47 billion in long term lease commitments for the next fifteen years even if revenue dries up tomorrow.

Don't look now, but economic conditions have begun to sputter in most of WeWork's markets, and it's years away from being capable of generating sustainable profit, much less free cash flow.

Worse, WeWork already has demonstrated spectacularly poor visibility and execution for years even with windfall support of solid economic strength and remarkably unending backstop investment capital. There's no reason to believe it can predict its performance during challenging economic conditions, especially if it has to stand on its own.

WeWork is a Money Losing Expert: It Is Known.

People who should know better have thrown hundreds of millions and then billions of dollars at WeWork for years, including its largest investor Softbank which reportedly owns a 29% stake. That's more even than WeWork co-founder and Chairman/CEO Adam Neumann who is said to own 22%.

Now they're all stuck since much of their investment was added at dramatically higher prices versus current IPO estimates which now indicate WeWork's value substantially below $15-20 billion estimates just last week.

That's because these "smart money" chiefs continued to invest in multiple funding rounds which dramatically increased WeWork's market value even as it dramatically and repeatedly trailed management's flamboyant projections for revenue, profitability, and free cash flow.

Here, for example, are the company's revenue and profit projections as presented in WeWork's October 2014 pitchbook, which was obtained by Buzz Feed News. Note spectacular revenue growth estimates with particularly robust EBITDA margins growing from 19% in 2014 to 36% by 2018. Cash was expected to remain healthy at 8-10% of revenue.

WeWork didn't report in its S-1 filing how the numbers actually landed in 2014-2015, since it covered only some, but not all of its financial performance as far back as 2016.

But there's enough there to show that WeWork's projections during its five-year capital-raising spree were way off, which should have been obvious to prospective and current investors well within the first year or two.

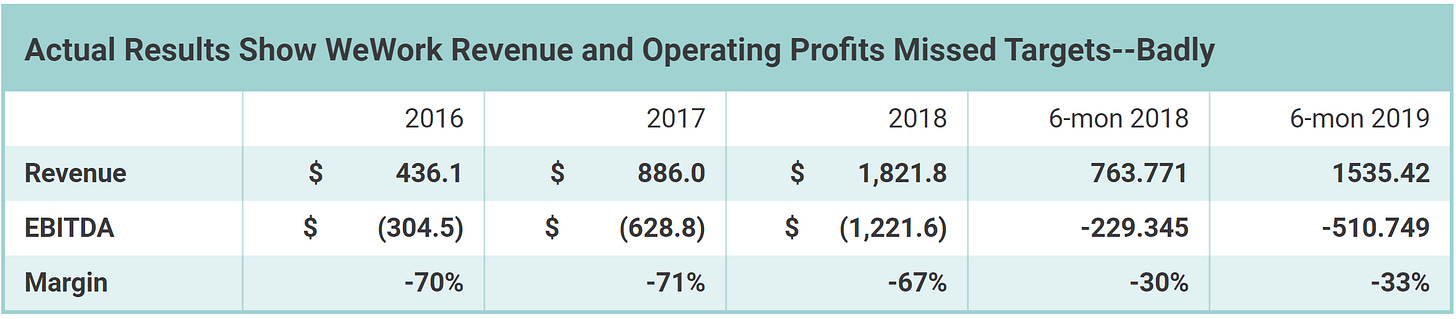

As the chart shows, revenue projections fell far short of the company's ambitious claims. For example, revenue was targeted at $715 million and $1.6 billion, respectively, for 2016-2017. In reality, revenue never got near $1 billion until 2018 when membership sales finally topped $1.6 billion. More disturbing was the severely negative EBITDA every year versus projections for strongly positive results plus improving margins to support growing profitability.

Here are WeWork's forecasts for cash flows from the same presentation. Look, Mom! Persistent and rapidly growing profits and strongly positive cash flows from operations projected plus accelerating free cash flow from 2015 forward that grows to more than 6% of targeted revenue.

Again, the outlandish 2014 projections were enough to strain WeWork's credibility, but by mid-late 2015 it should have been clear to current and prospective investors that WeWork would miss its 2016 targets for revenue and profits, badly. What to do? Management pushed it's amazingly increased $1 billion revenue estimate for 2016 forward to 2017, which it also missed--badly, and would continue to do in subsequent years.

Nevertheless, the capital WeWork raised on the strength of such projections escalated at blinding speed. The December 2014 capital raise boosted its implied value to $5 billion from $1.5 billion just ten months earlier in February. The Wall Street Journal said the December round was "co-led by funds and accounts managed by T. Rowe Price Associates Inc., clients of Wellington Management, and Goldman Sachs Group, according to WeWork. Investors from prior rounds including JPMorgan Chase & Co. (also longtime lead banker for WeWork and Neumann), Harvard Management Co., and Benchmark also participated."

These are the folks who believed WeWork would grow revenue from $74 million in 2014 to $2.9 billion in 2018 or some 38x higher in just four years, with run-rate revenue spiking 30x from $121 million to $3.7 billion. They swallowed whole its $5 billion market valuation--67x revenue as of December 2014.

They weren't alone. Subsequent capital raises boosted WeWork's valuation to $10 billion by June 2015, to $16 billion by March 2016, and to $16.9 billion by October 2016, which was 10x the $1.7 billion in capital WeWork had raised mostly in two years.

So, amazingly, WeWork's persistent failures in forecasting and execution apparently didn't even smudge its luster with its private equity fanbase. Instead, Softbank investments took WeWork's valuation from $16.9 billion to $47 billion in just over two years.

Softbank's first investment was surprising given it had rejected WeWork for years as overpriced and not a tech company--which was true. But that was before SoftBank’s eccentric Chairman Masayoshi Son nevertheless decided WeWork felt like a great fit for the bank's new tech-focused Vision Fund, overruling significant internal objections to make it happen. Son prefers to listen to his gut instinct versus the buzz-kill from actual analysis, even when making multi-billion investments for Softbank and Vision Fund. Son told shareholders at the company's 2018 annual meeting, “Feeling is more important than just looking at the numbers. You have to feel the force, like Star Wars.”

In August 2017, Softbank invested a stunning $4.4 billion, reported at the time at "one of the largest single slugs of capital ever in a venture-backed startup." This bought Softbank two seats on WeWork's board and a share in accountability for whatever came next. Three more investments totaling $9 billion followed into January of this year, which landed WeWork at $47 billion.

Vaulting WeWork to such a rarified value was self-reinforcing for Son, even if this alarmed Softbank's own investors. He actually wanted to spend another $16 billion to buy all of WeWork in December 2018, when it was valued at $45 billion, but Vision Fund's largest investors balked. Even Softbank's head of Vision Fund expressed doubts in 2018--after Softbank's investment had driven WeWork's value to $40 billion--saying “Maybe it’s overvalued, but I believe they’ll be a $100 billion company in the next few years.”

Or maybe not. Co-founder and CEO Adam Neumann, who has been anointed and enriched with extraordinary control over the company regardless of its performance, arguably has the most to gain if it does. He cashed out $700 million of his stake in July, less than a month before the IPO was announced while WeWork's value was at its peak. Its value has crashed by at least 78% since then.

Willful blindness, greed, complacency, and happy vibes gut feelings. This is how WeWork became the most highly valued venture-capital backed firm in the U.S. at $47 billion, a multiple some 10x higher versus IWG with precious little support to justify why it's worth that much.

That's because it's worth far less.

Enter Reality

Here is the sobering view of WeWork's dismal performance since 2015:

As shown in earlier charts, revenue growth has fallen well short of management's targets. But WeWork's more pressing concerns are escalating costs which far outpace revenue growth and drain its cash, which management has gotten more creative over the years to explain, without much success.

Here are some troubling observations about WeWork's continuing trends:

EBITDA has remained severely negative, even as WeWork adjusts it with substantial add-backs for restructuring charges, stock-based compensation, reported noncash expenses, and unusual items. Such adjustments are substantial--adding more than $1 billion to GAAP EBITDA. Even WeWork's generously defined adjusted EBITDA indicates severe deterioration continued through the first half of 2019 and likely through yearend despite higher revenue.

WeWork excludes stock-based compensation from EBITDA even though it increasingly uses stock even to pay contractors for services, presumably to preserve its evaporating cash.

To get around chronically negative EBITDA, WeWork invented a dubious Contribution Margin calculation supposedly designed to reflect a closer picture of run-rate operating profit on core operations without growth expenses like "pre-opening location expenses" and "growth & new market expenses." The trouble is this contribution margin also excludes core operating expenses like general & administrative, sales & marketing, and other operating expenses and key costs, so it actually reveals only that WeWork will obfuscate if it can make the numbers look better.

How much better? WeWork reported an adjusted contribution margin of $605 million for the trailing 12 months ended June 30th versus -$910 billion in creatively adjusted EBITDA and -$1.95 billion in GAAP EBITDA. The difference in these numbers is stunning, and it's easy to see which is more aligned with the much larger than expected $2.1 billion loss ($1.67 billion after minority interests).

Lease costs are WeWork's most expensive and they are going up no matter what given its now $47 billion in lease obligations. Rent expense was about 65% of revenue at $1.7 billion for 2018. Accounting changes for 2019 make it harder to track, but I estimate this is up at least 20% for 2019.

Margins look worse, especially adjusted contribution margin which was down 230 basis points to 23.3% versus yearend, which signals rapidly worsening losses despite revenue growth.

Cash burn is intensifying from stifling losses and burgeoning capex, a big problem which WeWork can only support by borrowing and selling equity. With capex now running roughly equal to revenue, WeWork burned a whopping $2.9 billion in cash after capex for the 12 months ended June 30th. This was only partly offset by $876 million collected from tenants to fund improvements as agreed--and 100% funded by debt and equity raised over the last year, as WeWork has done over its entire history.

All that borrowing and selling of equity hasn't even been enough lately. Reported cash was down nearly $300 million versus 2017, even after including $3.75 billion invested by Softbank plus $702 million WeWork sold in high yield bonds plus $750 million sold in equity--$5.5 billion consumed.

Virtually all of this was depleted in the first half of 2019, since all the $2.47 billion in available cash reported as of June 30th can be traced to another $2.5 billion investment from Softbank.

Reported available cash is not actually available. WeWork includes cash belonging to its variable interest entities (VIEs) in reported consolidated available cash--that's not WeWork's cash to spend. Neither are customer deposits, which are held until their expected return to customers. Stripping out these amounts from already disturbingly thin reported numbers reveals effective available cash actually critically low: just $521 million for 2018 versus $1.74 billion reported. Effective available cash as of June 30th was more than $1 billion lower versus reported at $1.4 billion (and only up versus December 31st because of Softbank's investments).

If WeWork completes its IPO and then is able to close the $6 billion arranged in new credit facilities, it will be required by covenants in the new bank debt to pony up additional restricted cash to back its letters of credit by 100%.

"Under the 2019 Letter of Credit Facility that we expect to enter into concurrently with the closing of this offering, we will be required to deposit cash collateral in an amount equal to the face amount of letters of credit issued under the facility. Accordingly, we expect our restricted cash supporting letters of credit to increase following the closing of this offering."

WeWork S-1, 8/14/19

Given the $1 billion currently outstanding in letters of credit, that means excluding more as restricted cash which leaves pro forma effective available cash at just $1 billion--not even enough to get through one quarter.

That's not all, WeWork expects to immediately take out the other $1 billion to be available in the new $2 billion letters of credit facility, which will then require another $1 billion in restricted cash set aside, and so on, and so on.

If You Can't Take The Heat...

Given how fast WeWork blazed through $5.5 billion of invested and borrowed cash in 2018, plus another $2.5 billion this year, it's easy to see why WeWork is urgently trying to get the IPO closed.

But just because the company needs fresh cash, pronto, doesn't mean it's a good idea for investors to oblige. It's also obvious that massive losses and severe cash burn will likely continue through at least another couple of years since core operating expenses and cash obligations actually are much stickier than management has projected.

So we can see why its bankers and large investors are concerned, as they should be.

How do we know WeWork's banks are spooked? Pending pricing on the new credit facilities is substantially higher versus its existing facility signed in 2015 to accommodate substantially higher risk--and this was before the working equity valuation plunged by 78%:

The $4 billion term loan is tentatively priced 250 bps higher at L+475, and the term was reduced to three years versus five years on the old deal.

The $2 billion letters of credit facility was tentatively priced at L+100 even with WeWork required to hold 100% of the draw in restricted cash.

The facilities' pricing also incorporates substantially higher LIBOR versus 2015, which adds another 182 bps to current pricing.

Then there's WeWork's equity valuation, which has become a moving target--downward.

We presume WeWork's bankers and legacy investors, which include many of the same parties, finally have acknowledged substantially lower expectations for revenue and profits, given tumbling equity valuations that have leaked out of the past couple of weeks. Yet we still shouldn't trust, based on past history, whatever valuation the dealmakers come up with now.

I always have been skeptical that WeWork is worth a higher valuation than IWG, for example, which trades at roughly 1.5x revenue and has much stronger operating metrics and financial condition. Given WeWork's weaker and highly volatile operating performance versus the increasing likelihood of more difficult business conditions, there's a good chance it will continue to trail expectations and its own guidance. If so, that means more bad news ahead through yearend, with 2020 probably little better. With the pace of revenue growth likely to slow while cost pressure still high and likely increasing, I also see substantial cash consumption continuing.

So I value WeWork's equity at 1.5x estimated 2019-2020 revenue of $3.3-5 billion, or $5-7.5 billion.

Bondholders, Beware of Plan B

WeWork's IPO is in jeopardy. There's also a good chance it doesn't come at all for the foreseeable future.

Yet it still needs cash, and we now can see the $9-10 billion it was trying to raise with $3-4 billion in stock and $6 billion in new borrowing could be depleted in a year or two at best. It doesn't have cash to spare to also pay off $670 million in bonds that don't even mature for another six years. That's ten years in WeWork projection time.

Instead, at recent prices near 102.8, 7.3% ytw, WeWork bonds actually are trading at a lower yield than Tesla Motors (TSLA US) even though the company is in much worse shape--which is remarkable (see Tesla Q219 10-Q Notes and Big Red Flags and Tesla’s Cash-Strapped Shanghai Plant Construction Is Hurtling Forward--What Could Go Wrong?. And given how hungry investors are for yield, it probably can get the deal done with much less fuss and thus increase its annual costs by only slightly more than it's paying in "other" operating expenses.

So WeWork may elect to come back to the bond market in coming weeks, before it reports what I suspect could be disappointing third-quarter results.

If so, I estimate it could raise $2 billion or more in new unsecured notes, of course not covered by assets or even a hint of healthy free cash flow generation for years. This number plus probably another $750 million to $1 billion from Softbank (the amount it was throwing into the IPO) likely will be enough to convince the banks to go forward with the new credit facilities which then will bury all WeWork bonds below secured debt that has a superior claim to virtually all tangible assets the company owns. (The meager consent fee the company offers so existing bondholders will allow this will be woefully inadequate to compensate for such increased risk).

No, thank you.

WeWork 7.875% senior notes were seen at 102.8, a remarkably low 7.3% ytw/540 bps given its appalling credit metrics and dismal prospects. Upside potential is limited at best versus downside risk which could be 10-15 points lower in short order. Rating: Sell.

Contact Us:

Disclaimer

This publication is prepared by Bond Angle LLC and is distributed solely to authorized recipients and clients of Bond Angle for their general use. In addition:

I/We have no position(s) in any of the securities referenced in this publication.

Views expressed in this publication accurately reflects my/our personal opinion(s) about the referenced securities and issuers and/or other subject matter as appropriate.

This publication does not contain and is not based on any non-public, material information.

To the best of my/our knowledge, the views expressed in this publication comply with applicable law in the country from which it is posted.

I/We have not been commissioned to write this publication or hold any specific opinion on the securities referenced therein.

Bond Angle does not do business with companies covered in its

publications, and nothing in this publication should be construed as a solicitation to buy or sell any security or product.Bond Angle accepts no liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect, consequential or other loss arising from any use of this publication and/or further communication in relation to this document.