What Tesla Can Learn From Navistar About Arrogant Management, Serious Mistakes, and Survival

Tesla Is Not the First To Be Damaged Most By Its Own CEO

Tesla Inc. (TSLA) has become disturbingly troubled, mostly because of serious mistakes which seem to be increasing.

Navistar International (NAV) knows plenty about catastrophic failures of its own making--and how to come back from the resulting smoldering wreck without resorting to bankruptcy.

Here’s how Navistar achieved its remarkable turnaround by surmounting even worse problems than Tesla is facing right now—starting with replacing its embattled CEO.

Turning up the heat

I warned in my last report Musk is Tesla’s biggest problem, and one it’s least likely to solve (see Tesla - Dave’s Not Here and Musk Won’t Leave). The pressure has only increased since then.

Two days ago news broke that the US Department of Justice has launched a criminal fraud investigation looking at Musk's asinine announcement by tweet on August 7 that he planned to take the company private at $420, "funding secured" (see "Tesla Take-Private Plan: Shoot First, Answer Questions Later (If at All"). This joins the SEC probe into the matter launched last month.

As it turned out, Musk actually had no deal, no buyers, no funding, not even a supportable price worked out.

He hadn't consulted with Tesla's feckless board or the company's largest investors or even financial advisors, and once he did he discovered it was best to abandon the whole idea (see "Tesla’s Take-Private Plan – Never Mind"). Tesla has lost as much as $20 billion in market cap since the end of the second quarter.

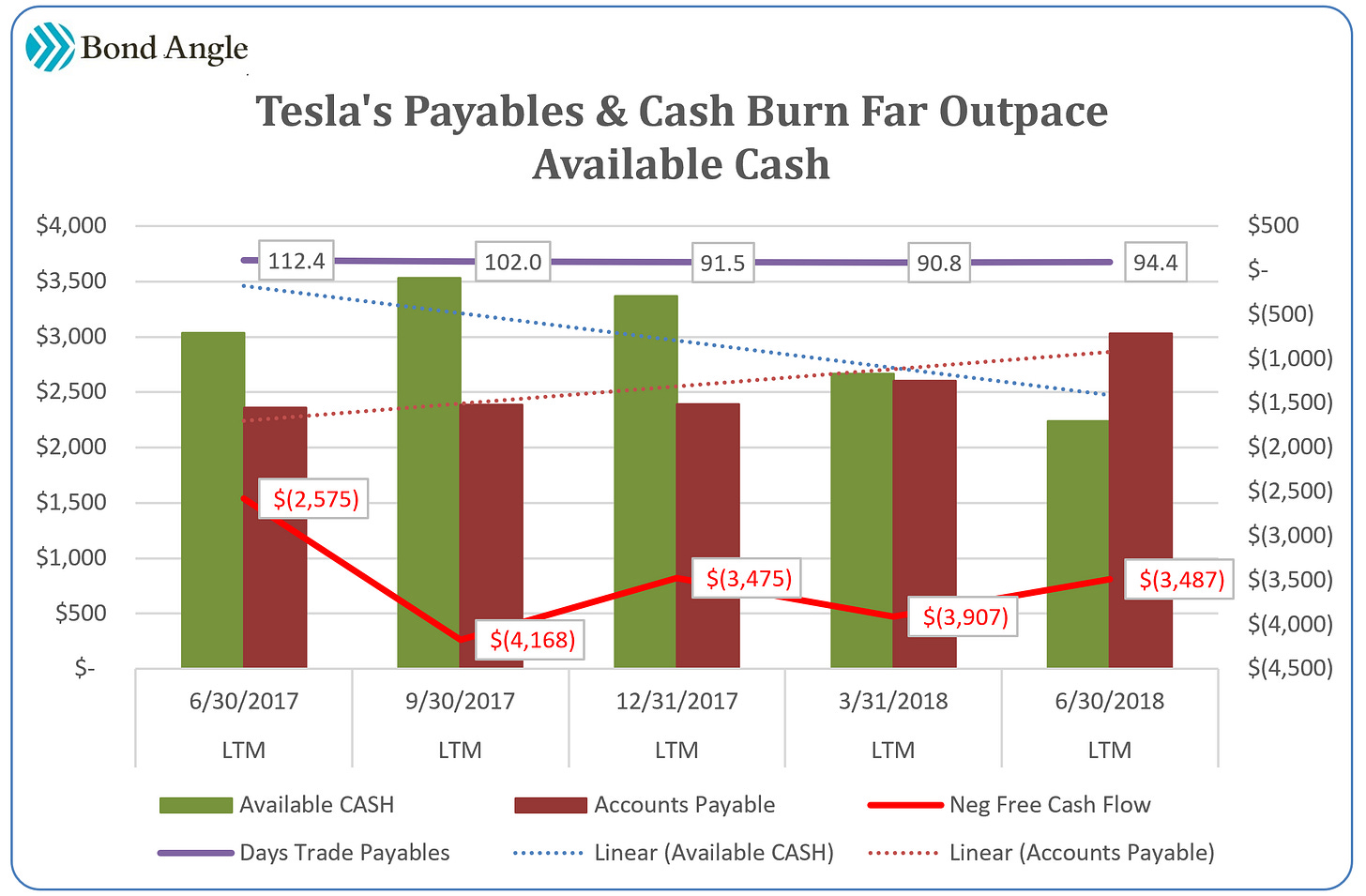

Tesla also is losing vital strategic management with alarming frequency. Bloomberg reported Thursday night the presumably abrupt resignation of Liam O'Connor, Tesla's Vice President, Global Supply Management, who no doubt has been struggling mightily to juggle the company's more than $3 billion in chronically overdue accounts payable.

Recall last month the Wall Street Journal reported Tesla's suppliers are worried it might be going bankrupt, especially after it has stretched payments out for months and even asked some suppliers for cash back.

No worries. Musk told the WSJ “We are definitely not going bankrupt.”

Ok, but Tesla also just lost yet another finance executive with the departure just last week of Justin McAnear, Vice President of Worldwide Finance and Operations.

He followed the sudden exit last month of Tesla's brand new Chief Accounting Officer Dave Morton who left after less than a month, walking away from a $10 million hiring perk. His predecessor just left in March.

Bottom line: Tesla is losing top executives key to the puzzle of its dwindling liquidity, just as its operations are becoming increasingly distressed ahead of hefty debt maturities it can't afford to repay.

This may signal their discomfort with potential "irregularities" in Tesla's accounting or compliance or management oversight that may surface as problems later with audited financial results for the year.

Whatever the reason, Tesla is losing key executives just before the close of the critical third quarter when it expected to prove it is sustainably viable.

Also catching my attention in the third quarter:

Tesla's demand reportedly is too strong to meet in a timely manner--saying it has evolved from "production hell" to "delivery hell"--and yet it recently announced it can offer immediate deliveries of Model 3s on a first-come, first-serve basis all over the country, presumably to juice sales before quarter-end (and possibly to help offset fading sales of Model X and Model S, as I expect).

Tesla can't deliver enough cars to meet said unsatiated demand when it sends line workers home well shy of weekly production targets--it has yet to meet targeted goals of 5,000 Model 3s consistently produced per week, for example, which was the goal for the second quarter. One explanation is it may be forced to cut costs to preserve cash.

Tesla said it paid down $500 million in revolver debt--which isn't due--early in the quarter, but said it will borrow it back before quarter-end to bolster cash. Was this repayment voluntary or are Tesla's banks getting worried? Remember the banks get substantially more financial information than we all get in public SEC filings, and they get it monthly versus quarterly.

I get skittish when banks get worried.

We are about to have the most amazing quarter in our history, building and delivering more than twice as many cars as we did last quarter.

Elon Musk, September 7, 2018

Sure, but given Musk's track record, there's good reason to be skeptical this might happen, or that he's not telling the whole story about what's going on.

But Is Telsa headed to bankruptcy?

"Tesla CEO Elon Musk is a nice guy who doesn't know how to run a car company," says Bob Lutz, former vice chairman of General Motors Co (GM). "It's an automobile company that is headed for the graveyard,"

Not necessarily.

Bankruptcy is a draconian solution which immediately sets equity and asset value on fire, squeezing usually hapless bondholders to death when the horse trading begins.

However inept Musk is as an operator, Tesla is a valuable brand with commanding market share and promising potential in a rapidly growing niche, so there is considerable support for its continuing operations which are indicated to improve significantly over the next year, albeit likely at a slower pace versus market expectations (see my forecast at the end of this report).

If so, its debt load will become increasingly manageable without substantial recapitalization.

Tesla also is easily as valuable, if not more, versus other car companies sold over the years, some multiple times; e.g. Land Rover, Jaguar, Maserati, Alpha Romeo, Chrysler, Fiat, Jeep, Citroen, etc. I could imagine Volkswagen AG (VOW GR) or Daimler AG (DAI GR) or Tata Motors Ltd (TTMT IN) as interested buyers of a distressed Tesla, for example--as long as Musk is not part of the equation.

Bankruptcy implies a hopeless scenario versus Tesla's problems, which seem short- to medium-term in duration and solvable. Tesla's main problems now (aside from management) are timing and execution; it's stumbling badly with both but could conceivably recover sufficiently to stabilize if given the flexibility to operate through the next 2-3 quarters. This assumes also that Musk's damaging propensities can be contained--which can't be assured.

In my twenty-five years covering distressed companies, I’ve seen many in arguably worse shape than Tesla achieve dramatic recoveries without resorting to bankruptcy. One remarkable turnaround is Navistar International (NAV) which, unlike Tesla, was a leading but mostly unexceptional competitor in a crowded field of heavy truck producers back in 2012 when it imploded as I projected due to self-inflicted calamity.

And like Tesla, both the problems and the fix came down to management.

How to Make a Small Fortune: Blow Up a Big Fortune

Navistar is far from the innovator Tesla is, but it did go its own way when the heavy truck industry was driven to reinvent a critical technology to reduce harmful gasses emitted from diesel engines. Things didn't go well.

For most of the first decade of the new millennium, the world’s makers of heavy and medium duty trucks and buses were busy designing and building engines with new emissions systems capable of passing the stringent compliance standard for maximum 0.20g oxides of nitrogen (2010 NOx standard) to be implemented by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) by 2010, limits which then were echoed across most of Navistar’s major markets around the world.

When the deadline came the industry was prepared to launch a new emissions system called Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR), which removes NOx outside a diesel engine by treating the exhaust stream in an external tank with an ammonia-based urea solution which combines with NOx to reduce harmful emissions by as much as 90%.

Navistar, however, did not meet the 2010 deadline. It had spent $700 million, some 2-3 times what its competitors had spent, developing its own Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR)system which redirects part of the exhaust gas back to the engine cylinders via the engine air intake. This oxygen-depleted exhaust gas blends with fresh air and is thus “cooled” before reentering the combustion chamber, lowering the temperature burn which reduces NOx emissions by up to 50%. Navistar added a diesel particle filter to help further reduce emissions by up to 90%.

It wasn't enough. And not only did EGR fail to meet EPA standards, it also created other problems like overheating the engine which made it vulnerable to other failures, weakened engine power, and impaired fuel economy.

That was bad news that Navistar kept quiet--it had other trouble brewing. Until 2012, revenue and profits had been growing and guidance was increasing.

Then in its first fiscal quarter of 2012, announced in March, Navistar revealed it was experiencing a disturbing increase in reliability problems with its existing trucks.

As a result, it was losing customers and warranty and repair costs also were spiking. Navistar's commanding market share in North America began to slip.

Wall Street was shaken but still on board. Neither Navistar nor Wall Street seemed inordinately concerned that the company was effectively gaming the system by selling its noncompliant engines via EPA emissions credits it was able to purchase and then by paying nominal noncompliance penalties when the credits ran out of just $1900 per engine--barely a whisker on a truck that sells for $130,000.

It took Navistar's competitors to finally shut down its free ride. Industry leaders joined together and sued the EPA for essentially favoring Navistar by allowing it to operate with an unfair competitive cost advantage.

A federal court agreed and vacated the EPA’s ruling which allowed Navistar to sell noncompliant engines seemingly indefinitely and subject only to a nominal penalty.

The court’s ruling came in early June, a week after Navistar released disappointing second-quarter results and reduced guidance for the year on fading sales and profit margins plus an even larger increase in reserves taken on worsening warranty and repair costs.

Court documents revealed that the EPA had agreed to interim penalties because Navistar threatened--in October 2011--that it otherwise would have to shut down production on Class 8 trucks and engines at an estimated cost of $3 billion.

That would have wiped out most of the Manufacturing segment revenue reported in the second quarter and more income than Navistar generated in more than a decade. Navistar told the EPA it could even be forced to leave the U.S. marketplace--which it probably would not survive.

Even before this shocking revelation, I already was wary after two years of increasingly vague and inordinately limited information from management about Navistar's dubious lack of progress with its engine tests for the EPA.

As of the fiscal second quarter ended April 2012, Navistar still had submitted only one of its proposed new engine models for testing--the 13-liter. There was no explanation of why the engine kept failing to comply or how far it was from meeting the compliance standard.

I came to believe, as I warned clients, that Navistar's EGR system would never pass EPA standards, that Navistar knew it, the EPA knew it, and management didn't have a Plan B.

I surmised that if Navistar was forced to abandon its noncompliant EGR and adopt SCR as I suspected, it would have to re-engineer every engine, truck, and bus it sold.

That could take years, while book value and sales prices were slashed immediately on its existing noncompliant inventory (which also backed its debt).

Navistar would have to buy more expensive EPA-compliant engines from a major supplier like Cummins Inc. (CMI) to generate sales during its transition while it started from scratch designing new engines on the fly.

Engines are not plug-and-play. The engine supplier must be willing to invest substantially along with Navistar to design and integrate their engines into Navistar's technology. Navistar must then wait for those engines to be produced and delivered while it also retooled its own production facilities accordingly.

The cost of such a disruption could be astronomical, Navistar's available cash and borrowing capacity already were evaporating, and leverage on its sizeable debt load was spiking.

Navistar's credibility was damaged and its solvency was threatened--not the best way to convince vital suppliers to stay involved. Moreover, Navistar was already losing customers because of dismal performance with its existing engines and trucks, the product of years of development.

What will they think about Navistar's new engines dropped into new trucks seemingly thrown together at the last minute?

It didn't help that management also had deliberately misled investors about how much trouble Navistar was in, as I suspected.

Navistar’s problems are not just hard to solve--it also seems to us like management has deliberately downplayed the seriousness of its situation and the increasing risk that solutions are not imminent.

"Unraveling" by Vicki Bryan, Gimme Credit LLC, 6/13/12

For these reasons, I warned clients that Navistar's once-rosy prospects suddenly had turned precarious. It did not seem to have the means to afford to absorb the calamity it had created or to fund its survival.

This, however, was not the prevailing view. Navistar's stock actually rallied to $30, though still down versus $47 early in the year, on news that venerable activist investor Carl Icahn had increased his dominant stake by another 1% to nearly 12%. The largest holder Mark Rachesky’s MHR Fund Management increased its stake to nearly 15%. Franklin Resources (BEN US) increased its stake to 18.8%.

Rumors were flying that they could be planning an attempt to force Navistar's board to replace its autocratic CEO Dan Ustian who had doggedly championed the much more costly and so far wildly unsuccessful EGR path against the advice of Navistar's own engineers.

Other speculation, much less credible in my view, was that players like Volkswagen or Paccar Inc (PCAR US) or even engine-maker Cummins were interested in buying Navistar.

Another rumor I thought was more plausible was that Navistar was hiring financial advisors though not, as the market speculated, to ward off unwelcome suitors.

I suspected Navistar was arranging potential asset sales to raise the pile of cash it soon would need, and if it wasn’t it should be.

As I noted to clients at the time, which then was cited by Herb Greenberg, CNBC, bankruptcy can happen for a company like Navistar that bet the farm on failed technology installed in every engine, in every truck, in every bus it sold—the foundation of all its revenue and profits. If it failed to get EPA approval, I warned, “that could be the end of the line. Navistar doesn’t have the cash or the borrowing capacity to absorb such a catastrophe.”

Things Got Ugly

Just a few weeks later on July 6, 2012, CEO Ustian made the first of several painfully awkward and even disingenuous announcements that the company was indeed abandoning EGR for SCR, the industry standard he had spent years bashing, while also trying to avoid admitting EGR was a disastrously expensive failure and that Navistar under his direction had gone terribly wrong.

Another mistake. Navistar’s customers and suppliers and employees and creditors and investors all realized Ustian had misled them and concealed the company’s increasing jeopardy.

Now he needed all stakeholders on board to help him save the company, but they had no reason to believe he could do it.

Less than two months after his July announcement that Navistar was dropping EGR, Ustian was out of a job, with horrific and, in some cases, irreparable damage was done and consequences played out over years like a slow-motion wreck.

By the end of 2012, Navistar had consumed over a billion dollars, which was funded by new cash from additional borrowing plus stock sold after Ustian was fired. The company reported a net loss of $3 billion versus $1.8 billion generated in net income for 2011.

Navistar’s leverage shot off the scale with debt up nearly 50% on EBITDA that plunged negative by $250 million versus $1 billion dollars generated in 2011 EBITDA when leverage also was just 2x.

The pain was far from over. It took a year for Navistar to launch its first EPA-compliant engine, and several more years plus another $1 billion in cash consumed and nearly $2 billion more in losses to get its new line of compliant engines and trucks rolled out.

Navistar's market share fell by more than half versus its former 30%, not helped by worsening performance of its older trucks which swelled warranty and repair costs by another $1 billion.

Navistar sold assets at a loss and closed plants it couldn’t sell. It lost revenue from millions of dollars in defense contracts where its bids were no longer welcome after decades of continuous business. Thousands of workers lost their jobs.

Navistar bonds had been trading near 110 early in 2012—they fell to 57 by the end of 2015, just before the stock troughed at $6. By then the company had been in recovery for at least year, but most investors just didn’t believe it would stick.

Tesla Can Learn From Navistar

Navistar blew itself up at a time when the heavy truck industry already was pressured by worsening economic trends and so crowded with more capable and better-capitalized rivals that there was a good chance no one would miss the company if it just disappeared. It almost did.

By comparison, the electric vehicle industry is thriving and likely will for the foreseeable future. Tesla is riding high as the dominant market leader with unit sales tracking 3-4 times higher than its next six competitors combined—and counting.

Its cars command premium sales prices and it still can’t meet burgeoning demand with unmet customer orders numbering in the hundreds.

There should be plenty of runway for Tesla to fix its current problems in time to better prepare for intensifying competition it likely will face next year.

And yet Tesla is, as Navistar did, squandering valuable currency with its most important stakeholders who worry it can’t deliver on its promises and could be in more serious trouble than it is claiming.

“If it keeps on raining the levee’s gonna break.”

Tesla is gambling dangerously with its suppliers—they have the power to shut it down, or not. No question about it. Tesla needs parts, unique as well as common. Signs are, however, that it is increasingly unwilling--or unable--to pay its suppliers on time or within any reasonable window, even for the notoriously ruthless auto industry.

Stories have emerged that Tesla is demanding 90-day to 120-day terms, as well as cash back on previously settled contracts. Mechanics liens filed against Tesla by suppliers have spiked 4-fold.

If Tesla is strapped for cash, which seems to be the case, the worst thing it can do is to cause suppliers to cut it off entirely unless it pays in cash up-front.

When Navistar was forced to abandon EGR, Cummins became it’s most important friend in the world. It needed more than Cummins' engines, it needed Cummins' strong reputation for reliability to help repair Navistar's shredded reputation.

But Cummins was not about to risk its own financial stability on an insolvent Navistar. It refused to sign a supply agreement with Navistar for nearly six months, and then only after Navistar had fired its troublesome CEO and raised nearly $1.5 billion in new cash to bolster liquidity.

I also suspected Cummins demanded to be on par with Navistar’s banks in claims to its assets before it agreed to spend one penny of its own cash to develop a new engine for Navistar.

Tesla's banks can save it. When Navistar killed EGR, it needed cash and lots of it. Fast. It took a couple of months of wrangling, but it finally convinced the banks to amend its revolving credit facility and allow it to borrow an additional $1 billion via a new term loan.

The banks required Navistar to pay off the modest borrowing on the previous revolver and whittled the availability on the new line, but the result was a net increase of nearly $800 million in debt with went straight to cash.

If Tesla is in trouble, it's likely already been negotiating with its banks for weeks, with these goals in mind:

Waive the covenant requiring minimum available cash at yearend to cover the entire $1.49 billion due in bonds maturing in 2019 plus a $400 million cushion. Tesla has projected positive free cash flow generated in the second half of the year, enough to also fund debt maturities.

However, it's also admitted to much higher than expected difficulties with production as well as deliveries so there's a good chance it could fall short. Waiving this covenant buys Tesla more time into 2019 to improve and potentially stabilize cash generation.

Loan Tesla more money, secured of course. Most of Tesla's assets already are encumbered as collateral for existing secured debt, but the banks, or another entity like Silverlake Partners (which Musk has been consulting) may accept as new collateral a block of Musk's dominant stake in SpaceX which has an estimated value of $20 billion. Musk owns roughly half of SpaceX, and even if he has also borrowed heavily against it as he has with his Tesla stock, there could be enough available to secure, say, $500 million in a new term loan--enough to refinance the $265 million in convertible notes due later this year and further bolster cash.

Tesla's bondholders can save it. Tesla's bondholders would suffer the most in bankruptcy or out, as I expect Tesla's banks and its powerful equity block would likely collaborate on some alternative recapitalization scheme to preserve their interests while squeezing bondholders to accept pennies on the dollar in a distressed debt exchange.

Push out maturities. A better idea for bondholders is for Tesla to tender for all the outstanding convertible bonds at par, sweetened with a generous consent fee, and funded with the issuance of a new senior unsecured note due after the existing 5.3% issue due 2025.

I expect a deal could get done at indicated pricing some 50-75 bps wide of the 2025 notes, which currently are trading near 7.9%. With debt maturities pushed beyond harm's way, Tesla might also successfully increase the deal size by up to $1 billion to further bolster liquidity, producing still manageable leverage improved in 2019 versus current leverage on strengthening EBITDA (see my projections for 2019 at the end of this report).

Make a deal to slash debt. Another idea I have suggested for some time is for Tesla to offer to exchange its convertible notes for stock early and at conversion rates much more generous versus terms in their existing indentures. This has the benefit of immediately slashing the bulk of Tesla's debt which promoting equity value as a result of the company's improved financial condition. Equity folks tend to have more trouble understanding why Tesla should be able to do this, but the whole point of a consent solicitation is to persuade bondholders to agree to change the terms of their indenture agreements, from covenant waivers to early repayment and even adjusting conversion specs. Anything is fair game; let's make a deal. This means this transaction also can be handled much like the consent solicitation above--very common in high yield markets.

Tesla's investors can save it, as long as Musk is no longer an obstacle.

With liquidity thus bolstered and the dire overhang of near-term debt maturities resolved, Tesla likely could raise additional cash selling stock, as Navistar did. Of course, Tesla will need to fully disclose the status of pending SEC and DoJ investigations and expected material impacts of mounting shareholder lawsuits. Such legal problems take years to play out and could be expensive to defend and settle down the road. Nevertheless, such overhangs tend not to deter companies from selling securities--just ask Navistar.

Tesla could attract a cash infusion from new equity investors or via a new joint venture with a willing partner to collaborate on some of its promising developments such as its autonomous mobility technology (say, with GM) or electric trucks (e.g. with Cummins).

Navistar benefited from a welcome $250 million cash infusion in connection with a new joint venture with Volkswagen via its Truck Group, once it was clearly on the mend. Volkswagen and Navistar agreed to collaborate in developing new technology and parts for current and future vehicles, with Navistar also able to immediately start selling parts compatible with Volkswagen's Truck products. I read this move at the time as a preamble for Navistar's ultimate sale to Volkswagen once it cleaned up its balance sheet. With Volkswagen now getting ready to spin off its Truck Group with an IPO and Navistar's dramatic improvement in operations and credit quality, this event could finally be near.

Tesla's board and top management, what's left of it, must go. Tesla needs seasoned management able to lead and develop and support effective strategies, which tend not to be those who can work for an autocrat like Musk.

Navistar quickly discovered that its biggest obstacle in initiating its recovery was its entrenched CEO Dan Ustian. Imperious and single-minded, he more than anyone was responsible for Navistar's direction and the EGR debacle was only the latest and most destructive of his many missteps.

Similarly, Navistar's board basically rubber-stamped his decisions just as Tesla's board has done. While there hasn't been obvious activist activity yet among Tesla's largest shareholders, Blackrock reportedly has voiced concerns about Musk's more recent shenanigans. It's going to take more than thoughts and prayers to effect convincing change; aggressive action needs to happen soon.

Even after sweeping changes in the management and the board, it took years for customers, suppliers, lenders, and investors to believe in Navistar's ability to recover, much less thrive—Tesla under new management might accomplish this in 1-2 years.

Tesla can survive without Musk, and it probably should. Tesla is no longer Musk's pet project, and it's increasingly clear it can't fulfill its best potential as a mature car company with Musk at the helm. Instead, he has become its biggest liability.

The best option is for Musk to remain attached somehow for his visionary and creative input, but he and what's left of his team must be replaced.

As I've said before, Apple (APPL) survived the loss of Steve Jobs, and it and Jobs were better for it.

As for Tesla…

A better idea would be assemble the plan to resolve liquidity pressure and debt overhang in time to announce as a balm to smooth over another disappointing quarter.

Tesla is coming to a showdown, exacerbated by Musk's alarmingly erratic behavior which seems increasingly more like desperation. Musk is squandering Tesla's invaluable mystique, which has kept fans and investors and creditors patiently on board for years while the company struggled to fulfill its promise.

It seems increasingly evident that third-quarter results, expected at the end of October, could fall short of Musk's ambitious guidance, again.

Tesla already has experienced higher than expected costs to meet delivery schedules on top of higher costs in pursuit of production targets which it still can't meet. Recall that 71% of cars rushed through production at the end of June had to be reworked, in addition to signs of quality controls curtailed and flawed cars increasingly delivered to customers. This suggests higher than expected margin pressure.

Indicated monthly unit sales figures seem to support that Model 3 deliveries seem to be tracking above production guidance of 50-55 thousand, as projected, but recent efforts to rush sales for quarter-end may also signal lower average prices realized versus expectations.

However, the surprising availability of inventory to support recent ad-hoc special sales events may also hint at increasing order cancellations--which also would pressure cash on hand. Moreover, I suspect Model X and Model S sales are tracking far lower versus the burst in sales at quarter-end logged last year, likely by enough for total deliveries to fall well short of targets.

Evidence of drastic measures to preserve cash via halted production and stiffing suppliers signal free cash flow generation could be falling meaningful short of guidance, pressuring already dwindling liquidity ahead of looming near-term debt maturities and possibly spooking Tesla's banks.

This all suggests higher costs and lower revenue than expected, with profits and free cash flow similarly below guidance and market consensus.

If so, Tesla will need a convincing explanation of how it plans to meet debt maturities over the next two quarters without depleting available cash necessary to sustain accelerating operations and capex.

I have sketched several ways Tesla can accomplish this even within my decidedly more skeptical projections versus market expectations for operating performance through yearend and the end of 2019--see my projection below.

The Forecast

I estimate third quarter EBITDA near $350 million (5.9% margin) on $5.9 billion in revenue (up 99%), versus $11 million in EBITDA (0.4% margin) on $2.98 billion in revenue. This assumes deliveries of just over 76 thousand, well below Musk's forecast for more than 80 thousand, with the shortfall coming from weaker than expected Model X and Model S deliveries.

I peg free cash flow improving to near breakeven or slightly better--not enough to assuage liquidity concerns--versus $1.4 billion consumed last year, and leverage worsening to 17.5x versus 13.9x.

Similarly, I expect continued improvement through yearend and for FY 2019 in revenue, margins, and free cash flow, albeit still well below market consensus.

This also assumes that debt due in 2019 is refinanced--with resulting leverage still significantly improved on stronger EBITDA.

Maintain “Underperform” on TSLA 5.3% Senior Notes due 2025; last seen at 86.7 (7.9% ytw; 480 bps)—up a couple of points over the past two weeks but still down nearly 4 points since 8/15/18 when I initiated coverage at “underperform.” Given Tesla's persistently volatile situation we still could see 3-5 points potential downside from here.

Contact Us:

Disclaimer

This publication is prepared by Bond Angle LLC and is distributed solely to authorized recipients and clients of Bond Angle for their general use. In addition:

I/We have no position(s) in any of the securities referenced in this publication.

Views expressed in this publication accurately reflects my/our personal opinion(s) about the referenced securities and issuers and/or other subject matter as appropriate.

This publication does not contain and is not based on any non-public, material information.

To the best of my/our knowledge, the views expressed in this publication comply with applicable law in the country from which it is posted.

I/We have not been commissioned to write this publication or hold any specific opinion on the securities referenced therein.

Bond Angle does not do business with companies covered in its

publications, and nothing in this publication should be construed as a solicitation to buy or sell any security or product.Bond Angle accepts no liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect, consequential or other loss arising from any use of this publication and/or further communication in relation to this document.