The Trouble With Tesla’s Arrested Development

Tesla's serious problems with manufacturing, quality control, & management oversight revealed—again

CNBC filed a scathing report this week detailing serious problems at Tesla (TSLA) GA4 tent, a supposedly temporary solution set up in the parking lot last year to ease Model 3 production constraints at the company's primary manufacturing plant in Fremont, California.

Even more troubling, as I long have warned, is that the problems CNBC uncovered really aren't new. Tesla's troubles also are no longer about being a quirky start-up still figuring things out as it goes. This is a $45 billion company now more than sixteen years old and more than a year into full-scale production capability for all of its models that it's expanding across the globe.

Tesla denies CNBC's findings, telling Business Insider they are “misleading” and that it has “dedicated teams” that “track every car throughout every shop in the assembly line.”

“In order to ensure the highest quality, we review every vehicle for even the smallest refinement before it leaves the factory. Dedicated inspection teams track every car throughout every shop in the assembly line, and every vehicle is then subjected to an additional quality control process towards the end of line. And all of this happens before a vehicle leaves the factory and is delivered to a customer. This applies to all areas of the factory, including our operations at GA4, and it’s why Tesla is able to build the safest and best-performing cars available today,'' the company said in a statement."

Gee, who should we believe?

If only there was mounting evidence from multiple sources showing Tesla has a long history of serious and escalating problems with its working conditions, plant safety, quality controls, and management oversight which already have cost the company millions of dollars in fines and settlements and yet no signs of being convincingly resolved.

Hint: there is. Lots, as I've been warning since last year.

Here We Go Again

It's only been a couple of weeks since Tesla surprised the market by reporting record deliveries for the second quarter. Now CNBC seems to confirm what I suspected: that the carmaker met its overly ambitious targets by again hurdling cars haphazardly through the production line in a frantic eleventh-hour rush.

And according to CNBC's sources, this resulted in cars out of the GA4 tent all but made with papier mache, baling wire, and duct tape.

Not really, but it may have felt that way to Tesla employees. CNBC found that production employees working in the GA4 tent were under such tremendous pressure to maintain targets that "they would frequently pass cars down the line that they knew were missing a few bolts, nuts or lugs, all in the name of saving time."

CNBC also found that supervisors told workers "to use vinyl electrical tape to make quick fixes" for "cracks on plastic brackets and housings." Employees said they purchased "the tape and other items for production associates" at Walmart.

One quick fix involved using electrical tape to secure "a segment of a white plastic housing where it holds “triple cam” [3-camera] connections in place inside of a Model 3" because "the edge of this plastic housing piece would frequently crack during installation."

Since these triple cams enable the Model 3 "to see the road, traffic lights, lane markings, and obstacles ahead," employees worried that "some of Tesla’s safety features — like Sentry mode, AutoPilot, automatic emergency braking, or full self-driving — may fail" if these taped up connections break.

That concern was shared by a former Tesla technician who had worked in the GA4 tent, and who examined the photos of the fixes employees provided to CNBC.

Tesla has denied these reports, telling CNBC it "hasn’t found evidence of electrical tape being used to make quick fixes in GA4, and would never officially condone or encourage it. And, as noted above, "the company also emphasized that its cars go through rigorous quality inspections before they leave the factory."

Perhaps this would be easier to believe if, as I observed in "Tesla's Plan B 2.0; Y Not," Tesla hadn't fired its entire Quality Control department at the Fremont Plant when it laid off 7% of its workforce back in January.

One fired Quality Control employee said at the time:

"My last repair on Friday was finding a rear fascia was missing a screw so if you pulled on it, it would pop out. I grabbed a drill, the screw, got down on my knees and made the repair myself.

No one would have known about it unless they tugged on the edges of the rear fascia like I had made it a habit to do. But I know once the car starts driving it would become unseated due to the wind pulling it out.”

Huh. Like this, for example? Reported a few weeks after Bumper-Bolt Man interviewed above was fired with the rest of Tesla's Quality Control department:

Indeed, reports have been coming in for a while now that Model 3 bumpers can fall off after the cars are driven in wind and rain.

So, perhaps don't drive a new Model 3 in the snow, wind, or rain. Check. Or in cold weather. Got it. (And maybe don't feed it after midnight, just to be safe.)

In any case, buyers have reported thousands of problems with Model 3 since its summer 2018 launch, ranging from annoying to serious to inexcusable failures.

This adds to persisting problems like battery fires, catastrophic suspension breakdowns, and wheels falling off which have been documented with now all Models 3, S, and X on top of their generally problematic and worsening reliability. Model X has carried a poor reliability rating from Consumer Reports ever since it was launched, while Model S lost CR’s recommendation in October 2018 mostly due to suspension problems. Consumer Reports recently was moved to retract its reliability ratings on Model 3 altogether.

And woe be to Tesla customers in need of repairs—the wait could be months.

The End Doesn't Justify the Means; It Exposes the Means

The point is, we've learned that Tesla rushing cars out the door to meet overly ambitious targets (usually set arbitrarily by CEO Elon Musk) generally means that won't be the last we hear of the cars produced that way.

Indeed, Tesla has been plagued with critical manufacturing problems for years, and they usually involve shortcuts and "quick fix" remedies such as CNBC reported that can have serious consequences:

Tesla stopped performing a critical "brake and roll test" in the summer of 2018, presumably to cut costs just as it was struggling with its long-awaited production ramp-up of Model 3.

An industry expert told Business Insider that "the brake-and-roll test is a critical part of the car's manufacturing process, taking place during its final stages. The test ensures that the car's wheels are perfectly aligned and checks the brakes and their function by taking the vehicle's engine up to certain revolutions per minute and observing how they react on diagnostic machines."

Tesla's mad rush to produce 5,000 Model 3s in the last week of June 2018 ended with 4,300 (86%) of those cars being so flawed they had to be reworked. Fast forward to yet another quarter-end rush in June this year, like every quarter this past year, but now using a dramatically reduced workforce following several rounds of layoffs and without a formal Quality Control Department. What could go wrong?

A lot, actually, given Tesla's troubling safety record. As I noted in "Tesla's Plan B 2.0; Y Not:"

Continuing layoffs could make such problems worse since Tesla has targeted for reduction its more expensive—and more seasoned—employees which included the elimination of its quality control department at its primary factory in Fremont.

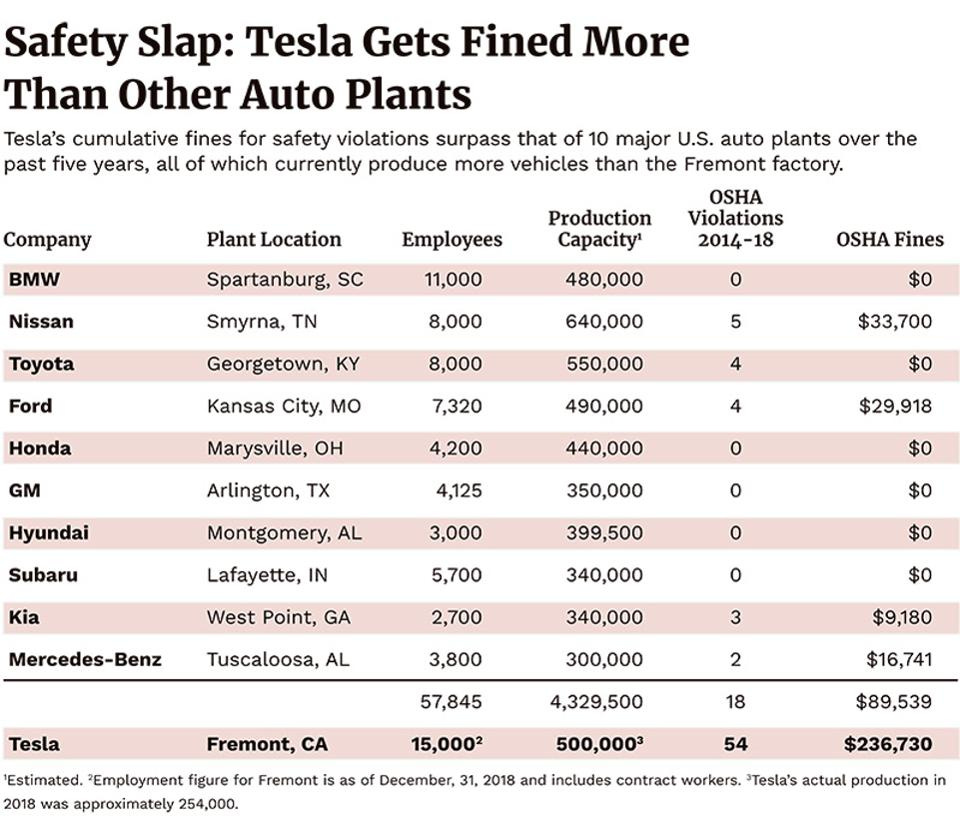

Insufficient staffing, weak quality control, and notoriously poor management oversight could aggravate Tesla's atrocious manufacturing safety record, already dramatically worse versus all other US automakers combined:

Source: Forbes

Employee injuries and job-related illness for 2018 were three times higher versus 2017's record pace. Bloomberg reported, "The sharp increase in the number of days away from work suggests a greater severity of injuries, said Deborah Berkowitz, who served as OSHA’s chief of staff under President Barack Obama and called the data “alarming.”

The rise in the average time missed — to 66 workdays in 2018 from 35 the year before — is a “red flag,” she said."

And yes, this included the GA4 tent facility, where California's Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal-OSHA) clocked Tesla for six violations between June and December 2018, including failure to "inspect GA4 for potential safety hazards."

Who's in Charge Here?

Whether it's quick fixes that fail or just chronically poor build quality, obviously the product suffers, angering customers and spooking buyers.

These problems are not new, so why are they still happening?

Managers who can't make effective and sustaining changes to fix Tesla's problems don't stay. This is, no doubt, due largely to Elon Musk's entrenched and clearly autocratic management. He doesn't listen to advice or suggestions, he doesn't like criticism, and he really hates rules (right SEC?). Musk doesn't follow rules, and he eliminates those who don't follow his rules.

He also tells employees to do the same, as he did in an April 2018 email where he advised employees to skip or walk out of unnecessary meetings, ignore the “chain of command” when it interferes with getting the job done, and "pick common sense as your guide" versus following a company rule that is "obviously ridiculous." Managers don't like it? Tough. "Any manager who attempts to enforce chain of command communication will soon find themselves working elsewhere."

So they go, willingly or not. Of the more than 30 senior executives known to have left Tesla over the past eighteen months, at least eight came from manufacturing, production, and/or engineering functions.

Does Musk's cavalier proclamations to employees promoting Tesla's flattish hierarchy mean enlightened management culture? Hardly. Employees have even less influence than their frustrated managers over their working environment or even dangerous conditions.

In fact, it seems comparatively easy to get fired from a Tesla job. Just use sick days or maternity leave, for example. The Guardian reports:

"Over the past few years, Tesla has faced numerous lawsuits, National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) charges and allegations that have included unfair firings, union-busting, and a work atmosphere that enabled racial discrimination and sexual harassment. In March, an NLRB settlement mandated Tesla post flyers that affirmed workers’ rights to organize at their Fremont, California plant. A few months later, workers at Tesla’s Buffalo, New York plant filed federal labor charges accusing Tesla of firing workers for union organizing."

Little is likely to change with Tesla's manufacturing practices, except perhaps for the worst.

The biggest tragedy of Tesla's remarkable story is that it has become its own worst enemy. And Tesla is Elon Musk.

It's Musk who divines Tesla's chaotic sales strategies, and Musk who makes Tesla's outrageous forecasts and sets overly ambitious targets for sales and production. He drives all product and production design and processes, and he drives away top executives with contrary views on, say, how to correct persistent troubles that result in flawed and potentially even dangerous results inherent in Tesla's manufacturing.

He also always seems to get his way, no matter what. Tesla's toothless Board of Directors, the SEC, the Department of Justice, the National Labor Relations Board, OSHA, numerous state governments and regulators and municipalities—all have failed to deviate Musk from his chosen path, even when his actions harmed the company and some, if not all Tesla's stakeholders.

So we should expect little if any improvement, if not worsening conditions, in Tesla's manufacturing plants in the US, and similar, if not worse, manufacturing issues cropping up when it opens its hastily built factory later this year in Shanghai, where management and regulatory oversight are substantially less intensive.

That's why CNBC's report was really a rehash of Tesla's long-standing problems with manufacturing, safety, and quality control, and why it probably won't be the last explosive exposé we will see going forward.

Killing the Golden Goose

Tesla's demand problems are not getting better, as I detailed again in "Tesla Q2 Deliveries Beat; Demand and Profit Trends Less Clear." Chronically poor build quality of now all its models could be a bigger negative factor than has been recognized.

Price cuts have been required to juice sales since last August, but haven't fixed the problem. It was expected that aging Models S and X would begin to struggle versus strong competitive offerings, including Model 3. The surprise was how fast years of pent-up demand settled once Model 3 arrived, along with its surprising and escalating quality and reliability problems—all of two quarters.

As I illustrated in "Tesla Q2 Deliveries Beat; Demand and Profit Trends Less Clear", Tesla has been slashing prices accordingly since last fall and yet still hasn't boosted demand to the vigorous pace seen in the last half of 2018. Were it not for Tesla's expansion late in the first quarter of Model 3 into China and Europe, Tesla's sales would be down so far this year versus the second half of last year when Model 3 was ramped-up to full-scale production.

Weaker than expected demand, I have speculated, is why Tesla surprisingly didn't affirm its ambitious guidance for 360,000-400,000 for 2019 despite reporting record deliveries for the second quarter that exceeded market consensus.

This seemed to be confirmed today with news that Tesla just announced more price cuts on all models in the US and China. Price reductions aren't necessary when demand is robust.

It's not Panasonic's fault. Tesla has blamed Panasonic, its long-suffering, and also most important supplier, for hurting Model 3 sales by not delivering enough batteries fast enough. The problem with this claim, as I first warned last fall, is that Tesla started developing excess inventory in Model 3 as early as last August because it proved unable to sell as many Model 3s as it could make, even at subpar production levels. (see "Telsa Party Today; Hang the Details" and "Musk and Weird Q3 Developments Are Driving Investors to Telsa's Rivals" and "Great Magic Trick Tesla; Now Do It Again").

Competition is a threat, from attractive rival cars as well as their more credible carmakers. Formidable competitors have begun to materialize, with more on the way, which offer serious challenges to Model 3. The trouble is all Tesla’s models have poor quality and reliability—especially given their still hefty price tags overall—versus sexy offerings comparably priced from, for example, Audi, Mercedes, Jaguar, Porsche, and BMW. Equally if not more important, all come from substantially more credible carmakers which offer superior quality and aftermarket customer service. Tesla buyers have trouble even getting their cars insured, wait weeks to months for repairs, and Tesla trade-in values are plummeting.

Persistent problems with Model 3 quality and reliability already have curbed the appetite for the pending launch of Model Y, which will share 75% of Model 3 parts and systems. Tesla also is unlikely to perform extensive field testing before launch, which could compound Model Y issues sufficiently to dampen sales soon after launch—as we saw with Model 3. Tesla's technical and production inefficiencies and its typically chronic delays may even render Model Y competitively irrelevant by the time its in full production in 2020-2021 (see "Tesla's Plan B 2.0; Y Not" and "Tesla: Now We Know the Y But Not the How" and "Tesla Bonds Go Boom").

Problems with Tesla's Pickup, whenever it finally shows up. I expect the Pickup to share many of the same problems I projected with Model Y, in addition to what could be a profound misread of what actual truck buyers really look for in a truck.

Carrying heavy cargo and/or pulling large, heavy trailers full of horses or boats and such (as I do) are certainly critical, getting to that rural local, spending the weekend in the middle of nowhere, and getting back without a recharge (because there's no supercharging station for miles around) is quite another challenge. Poor build quality and terrible reliability are deal-killers.

Tesla's problems are systemic and cultural, set by CEO Elon Musk who also refuses to accept guidance or blame.

Neither Musk nor Tesla's problems are going away any time soon. Indeed, it's more likely they expand with pressures from continued market expansion, new model launches, and the opening of Gigafactory 3 in Shanghai where there is even less regulatory oversight and later into Europe whenever that plant is built.

It's Tesla's way.

Maintain “Underperform” on TSLA 5.3% Senior Notes due 2025, down half a point since my last report to 89 (7.6% ytw; 575 bps). That’s a measly 96 bps of spread per turn of estimated leverage in 2019, woefully inadequate compensation for such a volatile issuer with such precarious prospects. Given Tesla's persistent uncertainty and escalating risks, we could see 5 or more points of downside from here.

Contact Us:

Disclaimer

This publication is prepared by Bond Angle LLC and is distributed solely to authorized recipients and clients of Bond Angle for their general use. In addition:

I/We have no position(s) in any of the securities referenced in this publication.

Views expressed in this publication accurately reflects my/our personal opinion(s) about the referenced securities and issuers and/or other subject matter as appropriate.

This publication does not contain and is not based on any non-public, material information.

To the best of my/our knowledge, the views expressed in this publication comply with applicable law in the country from which it is posted.

I/We have not been commissioned to write this publication or hold any specific opinion on the securities referenced therein.

Bond Angle does not do business with companies covered in its

publications, and nothing in this publication should be construed as a solicitation to buy or sell any security or product.Bond Angle accepts no liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect, consequential or other loss arising from any use of this publication and/or further communication in relation to this document.